What does the UN high seas treaty mean for protecting the ocean?

New York, New York – The world's first international treaty to protect the high seas was adopted by the United Nations on Monday, and contains landmark tools for the conservation and management of international waters. But what does it really mean?

The landmark environmental accord designed to protect remote ecosystems vital to humanity was hailed as a "historic achievement" by Secretary-General Antonio Guterres. The treaty that will establish a legal framework to extend swathes of environmental protections to international waters.

International waters – outside the jurisdiction of any single state – cover more than 60% of the world's oceans.

Ocean ecosystems create half the oxygen humans breathe and limit global warming by absorbing much of the carbon dioxide emitted by human activities. With so much of the world's oceans lying outside of individual countries' exclusive economic zones, and thus the jurisdiction of any single state, providing protection for the so-called "high seas" requires international cooperation.

The result is that they've been long ignored in many environmental fights, as the spotlight has been on coastal areas and a few emblematic species.

A key tool in the treaty will be the ability to create protected marine areas in international waters.

Currently, only about 1% of the high seas are protected by any sort of conservation measures.

Following more than 15 years of discussions, including four years of formal negotiations, UN member states finally agreed on the text for the treaty in March after a flurry of final, marathon talks.

The UN treaty, which will open for signatures on September 20, will go into force 120 days after 60 countries have ratified it.

"Countries must now ratify it as quickly as possible to bring it into force so that we can protect our ocean, build our resilience to climate change and safeguard the lives and livelihoods of billions of people," said Rebecca Hubbard of the High Seas Alliance.

Here are the key points of the text, officially known as the treaty on "Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction" or BBNJ.

What is in the UN treaty on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction?

The treaty begins by recognizing "the need to address, in a coherent and cooperative manner, biodiversity loss and degradation of ecosystems of the ocean."

These impacts include the warming of ocean waters along with their loss of oxygen, acidification, mounting plastics and other pollutants, as well as overfishing.

The text specifies that it will apply to waters beyond countries' exclusive economic zones, which extend to a maximum of 200 nautical miles from the coasts.

It also covers what is known as "the Area," shorthand for seabed and subsoil beyond the limits of national jurisdiction. The Area comprises just over half of the planet's seabed.

The Conference of the Parties (COP) will have to navigate the authority of other regional and global organizations.

Chief among these are regional fisheries bodies and the International Seabed Authority, which oversees permits for deep-sea mining exploration in some areas and may soon make the controversial move of allowing companies to mine beyond current test runs.

Currently, almost all protected marine areas (MPAs) are within national territorial waters. The treaty, however, allows for these reserves to be created in the open ocean.

Most decisions would be taken by a consensus of the COP, but an MPA can be voted into existence with a three-quarters majority, to prevent deadlock caused by a single country.

One crucial shortcoming: the text does not say how these conservation measures will be monitored and enforced over remote swathes of the ocean – a task that will fall to the COP.

Some experts say satellites could be used to spot infractions.

Individual countries are already responsible for certain activities on the high seas that they have jurisdiction over, such as those of ships flying their flags.

On the high seas, countries and entities under their jurisdiction will be allowed to collect animal, plant, or microbial matter whose genetic material might prove useful, even commercially.Scientists, for example, have discovered molecules with the potential to treat cancer or other diseases in microbes scooped up in sediment, or produced by sponges or marine mollusks. Benefits-sharing of those resources has been a key point of contention between wealthy and poorer nations.

The treaty establishes frameworks for the transfer of marine research technologies to developing countries and a strengthening of their research capacities, as well as open access to data.

But it's left to the COP to decide exactly how any monetary benefits will eventually be shared, with options including a system based on specific commercialized products, or more generalized payment systems.

What are the next steps for the UN treaty on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction?

The treaty will open for signatures on September 20, when dozens of heads of state will be in New York for the UN General Assembly.

It remains to be seen how many countries will decide to come on board.

Russia itself from the treaty as soon as it was adopted, declaring some elements of the text "categorically unacceptable".

NGOs believe that the threshold of 60 ratifications required for it to enter into force should be reachable since the High Ambition Coalition for the BBNJ -- which pushed for the treaty -- counts some 50 or so countries as members, including those of the European Union, as well as Chile, Mexico, India and Japan.

But 60 is far from the universal adoption – the UN has 193 member states – that defenders of the ocean are pushing for.

"Let's carry this momentum forward. Let's continue working to protect our oceans, our planet, and all the people on it," said UN General Assembly President Csaba Korosi.

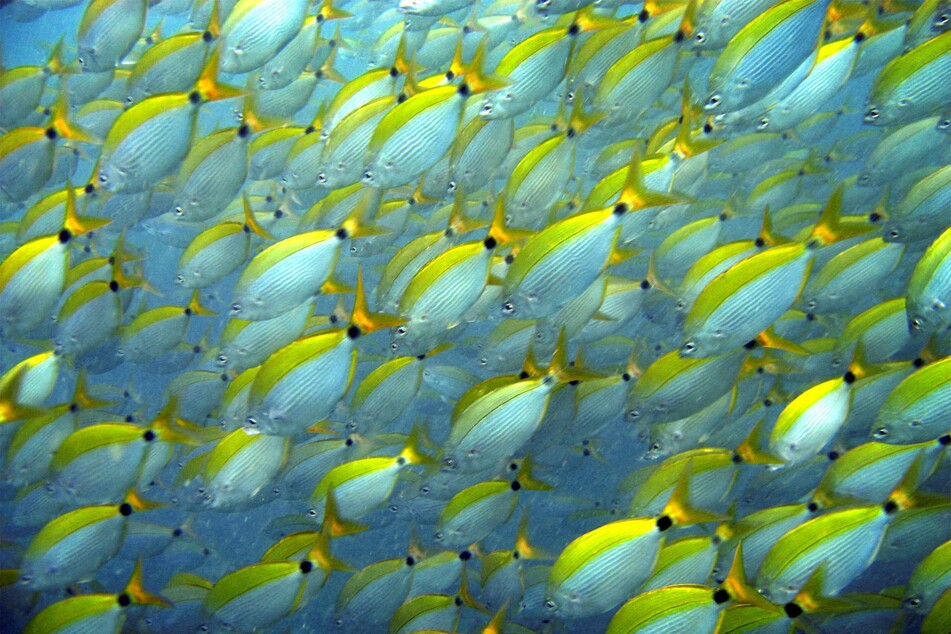

Cover photo: Collage: DANIEL SLIM / AFP & REUTER