World Reef Day: Will the last intact coral reefs soon be destroyed by climate change?

Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt - In honor of World Reef Day celebrated on June 1, we're taking a look at one of the many consequences of global warming: the major coral bleaching observed around the world. Yet, Egypt's coral reefs could defy the odds.

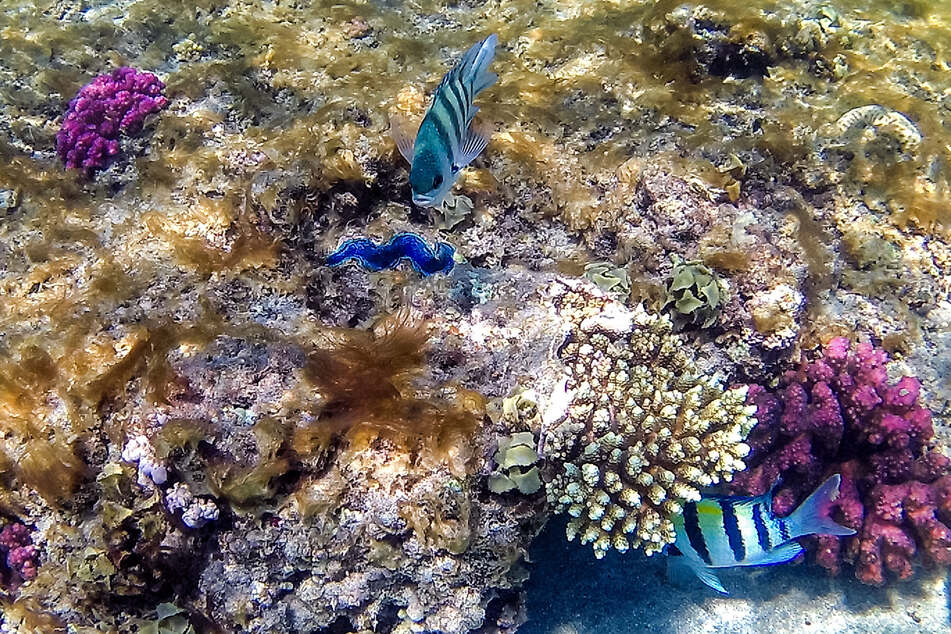

Along the coast of Egypt, where the UN Climate Change Conference was held in November 2022, there is a coral reef near Sharm El-Sheikh that is colorful and still largely intact.

Scientists say in a few years, it could be the world's only intact coral reef, thanks to the "climate memory" of its corals.

"We have sound evidence that this coral reef preserves the hope of humanity to maintain a coral ecosystem," said Mahmud Hanafy, a marine habitat expert from Suez Canal University, because the corals off Egypt's Red Sea coast are "very tolerant of water warming."

According to the National Ocean Service, coral bleaching occurs when water temperatures are too warm.

"Corals will expel the algae living in their tissues, causing the coral to turn completely white," they said. "Corals can survive a bleaching event, but they are under more stress and are subject to mortality."

From 2009 to 2018 alone, 14% of the world's coral reefs were destroyed by climate change, and were hugely affected by coral bleaching.

The Red Sea reef off the coast of Egypt accounts for 5% of the world's coral resources. Although it's been able to avoid most damage from coral bleaching, other human threats are troubling it: mass tourism and overfishing.

Experts are detailing why the fight to protect it, and coral around the world, is so crucial.

Coral reefs are experiencing danger from increasing heatwaves in the world's oceans

Corals cover only 0.2% of the world's ocean floor, yet they are home to at least a quarter of marine plant and animal species. More than 500 million people depend on corals for their livelihoods, to attract tourists, and to protect coastal areas from erosion.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)'s has warned that if global warming continues, there will be no corals left, at least in shallower waters, by the end of the century.

Even if the 2015 Paris climate agreement's goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees by 2100 compared to pre-industrial times is met, most of the world's coral populations are unlikely to survive because of increasing heatwaves in the world's oceans.

This summer alone, 91% of the Great Barrier Reef was affected by coral bleaching because of one such heatwave near Australia. Bleached corals can recover depending on the severity of the damage, but they do not survive recurring heatwaves.

Yet, Egypt's coral reef seems to have been an exception to most coral bleaching because of its uniqueness.

Will the Red Sea be the last protected zone for coral reefs?

Egypt's coral reefs have defied many heatwaves because of "a biological memory that has evolved over the course of evolution," explained Eslam Osman of King Abdullah University in Egypt's neighboring country of Saudi Arabia.

Together with other researchers, Osman has found out that coral larvae made their way from the Indian Ocean to the Red Sea via the Gulf of Aden at the end of the last ice age 12,000 years ago. In the process, they had to pass through "very warm waters" that would have acted like a filter. Only coral larvae that survived water as warm as 32 degrees reached the Red Sea.

In the warmer waters of the Red Sea off the coast of Sudan, coral bleaching from marine heatwaves has already occurred, but further north off Egypt's coast, the corals could "tolerate a temperature increase of one, two, or even three degrees," Osman said.

But because the corals in the Red Sea are more resilient than elsewhere, they need to be protected against other threats, Hanafy urged, citing the need for Egypt's Ministry of Environment to place the entire 150-square-mile coral reef under protection. The move would mean restricting both fishing and diving in the reef, and also, help prevent pollution in the waters around it.

Osman also sees Egypt's coral as a precious treasure and has stressed the need to protect it.

"You absolutely have to preserve the north of the Red Sea as one of the last protected areas for coral, because this area could serve as a breeding ground for regeneration projects in the future," he said.

Cover photo: KHALED DESOUKI / AFP