"No other choice": The Japanese Americans joining the fight for Black reparations

Los Angeles, California - The movement for Black reparations is gaining ground by the day, and TAG24 spoke with two Los Angeles-based organizers to learn about Japanese Americans' contributions to the fight.

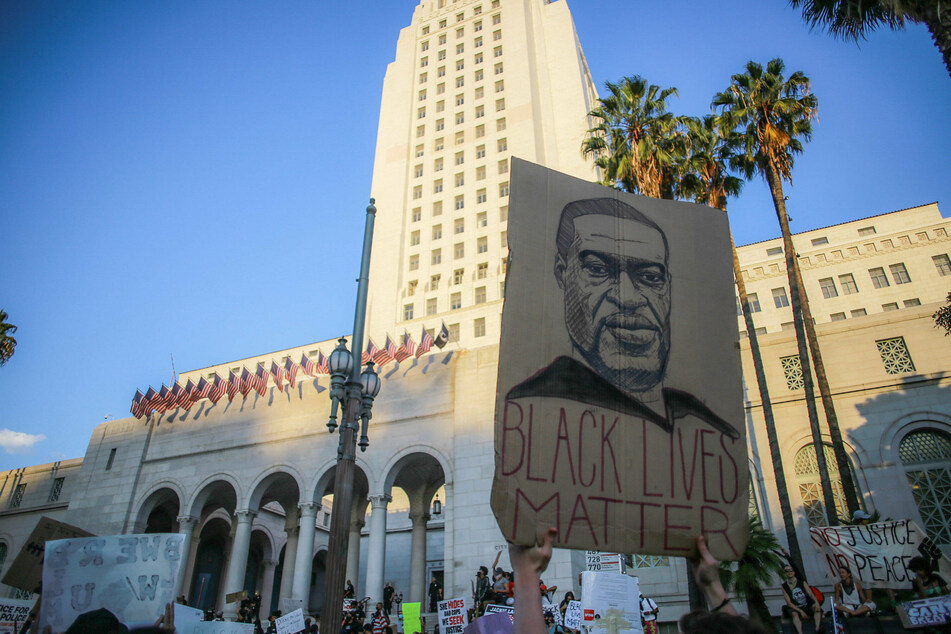

Since the murder of George Floyd, the push for reparative justice for Black Americans has seen an influx of support from people of all backgrounds.

State and local reparations commissions are popping up across the US, and in April, HR 40 – the Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act – received its first-ever House committee vote after more than 20 years.

The federal bill is now within 10 votes of being able to pass in the House, and activist groups across the country are working overtime to win over the last Democratic holdouts.

Included among those organizers are Japanese Americans, who successfully campaigned for their own reparations program after the forced relocation of around 120,000 people of Japanese descent to US concentration camps during World War II.

TAG24 sat down with two representatives of Nikkei Progressives and Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress (NCRR). The groups have formed a joint committee to fight for HR 40 out of Little Tokyo in LA.

Justice as a multi-generational struggle

Kathy Masaoka, a third-generation Japanese American, was involved in the campaign for Japanese reparations in the 1980s. Her journey began while enrolled in the first Asian-American Studies courses at UC Berkeley in the 1960s.

Before that, she said she felt "alienated" from Japanese-American history, from American society at large, and even from herself.

Reconnecting with the Japanese-American community in her college years inspired her to take a leading role in NCRR and the fight for Japanese reparations.

Kathy and fellow NCRR members won that fight, but with many other groups in the US still in need of redress, they knew their job wasn't done. They began campaigning for other marginalized communities, including Muslim Americans following 9/11.

As years passed, NCRR organizers recognized they had to get younger community members involved in the fight.

That's where Traci Kato-Kiriyama comes in. Her parents, interned as children at California's Manzanar concentration camp, taught her from an early age that she would learn more about history outside the classroom.

As an artist and community organizer, Traci has been instrumental in bringing younger generations into the fight for justice. In 2016, she helped establish Nikkei Progressives, which carries on the traditions of NCRR while also incorporating ideas from younger members.

Kathy and Traci emphasized the need for intergenerational communication and cooperation in their education and advocacy work.

Japanese-American reparations as an anchor

For both Kathy and Traci, their personal connection to the Japanese-American reparations movement informs their activism today.

"Japanese-American redress was the gift that kept giving because we learned so much," Kathy said.

Traci agreed, adding that watching the 1981 Commission on Wartime Relocation & Internment of Civilians hearings was a turning point in her life.

"It fought against every trope I had heard about Japanese Americans and Asian Americans in general, because I saw people who were publicly loud, angry, emotional, upset, and articulate – and they were doing it in community," she said.

"It's one of the driving forces for me because I understand what it is in my own family to feel bitterness from wounds that will never heal because of the fact that I have family who died before the awareness even of a redress campaign," Traci explained.

"I carry an anchor I know I'll always have. And that's fine, because that's part of my fire then for something like this," she said of her current HR 40 advocacy work.

The Japanese-American reparations movement led to the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. The law gave $20,000 to each surviving US citizen of Japanese descent who had been interned during the war. President Ronald Reagan also extended an official apology to the victims.

One year later, HR 40 was introduced in Congress for the first time.

Centering Black leaders

Though the Japanese-American struggle is of enormous personal significance for Kathy and Traci, both stressed that they don't want to make the fight for Black reparations about their own community's experience with detention.

"Nobody dictated to Japanese Americans what kind of redress we were going to get, and we're not going to do that for anybody else," Kathy insisted.

Instead, their work revolves around studying the history of Black oppression and building relationships with Black leaders and other identity and faith-based organizations across the country.

Through their long-term relationship-building, they are often called on to participate in specific actions, including sponsoring phone-banking initiatives and helping to organize HR 40 town halls.

Taking part in these activities has challenged Kathy to re-examine the terms of the Japanese-American program: "Looking at reparations today and how people are talking about it makes me look back on our reparations to say that, 'Boy, if really this country had been serious about undoing the wrong, the education part would have been a given.'"

"They would have automatically put this into the books for people to study and to learn. But it was up to us to have to do the education, to create the materials and all of that," she recalled.

There's no way but forward

Both Kathy and Traci stressed that fighting for HR 40 is necessary.

"There is no other choice," they said.

"Just as the commission hearings for Japanese Americans in 1981 were a real opportunity for us, as Japanese Americans, to begin healing and to learn, it was also a way for the whole society to learn," Kathy said.

"There's never comprehensive healing, but we have to at least attempt it," Traci agreed. "There is a stain on every part of this country because of slavery and its legacy. That's a heavy thing for all of us to carry. Consciously or subconsciously, we are carrying that."

"I don't care what anybody says. Even if they could give a crap about reparations, if they verbalize that, subconsciously there is duress because even in that pushing up against a resolution, there is an unease, there is a discomfort inside that person," she continued.

"I really believe in that saying: once Black folks are free, we're all free. Liberation is not just for one; it's for all. And all cannot be liberated if the one doesn't get it, because we're so interconnected and we share this space."

Kathy and Traci encouraged Americans of all backgrounds to get involved in the reparative justice movement, suggesting people take a look at the organizations in the Why We Can't Wait Coalition as well as state and local initiatives in their area.

"Ultimately, I don't think [Black reparations] will be achieved unless we have voices from all across the board, and the [Japanese-American] redress movement is a testament to that," Traci said. "We really did need a lot of folks."

Cover photo: Screenshot/Instagram/nikkeiprogressives