New Jersey Reparations Council shines light on environmental racism in seventh public session

Newark, New Jersey - The New Jersey Reparations Council (NJRC) on Monday outlined the historic and current harms of environmental racism in its seventh virtual public session.

The NJRC was convened by the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice and launched on Juneteenth 2023. It consists of dozens of experts organized into nine committees, all tasked with examining the state's legacy of enslavement and racial discrimination and developing a slate of policies to address those harms.

The NJRC has conducted six previous public sessions as it prepares to deliver a final report next Juneteenth:

- History of Slavery in New Jersey

- Segregation in New Jersey

- Faith and Black Resistance

- Health Equity

- Public Safety and Justice

- Democracy

The seventh meeting on environmental justice took place as communities across the South face their second climate disaster in two weeks, as Category-5 Hurricane Milton barrels toward Florida in the immediate aftermath of the deadly Hurricane Helene.

"What we are talking about today is really about lives and human suffering and human thriving," said council co-chair Taja-Nia Henderson of Rutgers Law School.

"The stakes could not be higher," she added.

Chattel slavery and climate catastrophe

Tracing the roots of climate catastrophes in the US today requires looking back to the origins of the country, founded upon a system of chattel enslavement.

"Slavery was a white supremacist and capitalist logic predicated on what we call the chattel principle, which was an extractive logic [...] that saw Black people as disposable labor forced to work land also seen as disposable," explained Mia Charlene White, assistant professor of environmental studies at The New School.

New Jersey, known as the "slave state of the North," was no exception. From the earliest days of white settler-colonialism in the region, Black people were forced to labor in agriculture, construction, manufacturing, and other industries, driving the US' ascendancy as a global economic superpower.

Southern states became major consumers of industrial products developed in the Garden State by enslaved people, including rubber, clothing, shoes, as well as glass, leather, and iron goods.

"The industrial products and practices of New Jersey industry, the same industries that frontline [environmental justice] activists have been organizing around for many decades, actually became tied to the preservation of slavery in the nation," White said.

The legacy of environmental racism today

The treatment of Black people as expendable continued even after the formal abolition of enslavement through disinvestment, surveillance, displacement, and other harmful policies.

Segregation, redlining, and industrial zoning led to the concentration of Black and brown people in ecologically vulnerable areas seen as undesirable by white residents.

Lower property values in deprived and redlined communities have contributed to lower municipal revenues, translating to less investment in schools, property, infrastructure, and social services.

Today, these neighborhoods disproportionately host sludge, toxic waste, sewage treatment, and other polluting facilities, while the system of racial capitalism has allowed a privileged class to accumulate generational wealth at their expense.

This reality also has detrimental health impacts for Black New Jerseyans, who have a lower life expectancy than white residents on average.

"The legacy of industrial toxicity means that the very air, water, and soil are harmful to Black people, and that is a direct result of the isolation, the policies that have been put in place, and the ways in which these communities are surrounded by toxicity by design," said Nicole Miller, vice president of the New Jersey Progressive Equitable Energy Coalition.

"The reality of sacrifice zones is not accidental. It is a direct result of the deliberate policies and practices that lead us to the lived experience of people in urban communities in New Jersey today."

A new path forward through reparations

Tackling the crisis of environmental racism is an urgent priority that must no longer be ignored.

"Reducing the amount of pollution in these neighborhoods is literally a matter of life and death," warned Nicky Sheats, director of the Center for the Urban Environment at the John S. Watson Institute for Urban Policy and Research at Kean University.

Reparations, he said, are a critical piece of the puzzle when it comes to addressing the cumulative impacts of racism and climate destruction enabled by federal, state, and local governments.

A comprehensive program should include climate change mitigation policies and mandatory emissions reductions. Such measures would help to fight climate change as well as to address disparate local pollution loads.

Vanessa Thomas, an environmental justice organizer with the Ironbound Community Corporation, also called for the closure of polluting facilities, which should be held accountable for the damage they have wrought.

"The flooding of Black communities with pollution has got to stop before we can begin the process of building anew," Thomas said.

"[Environmental justice] reparations really looks like creating a pathway for those exact facilities to bear the cost of their pollution," she continued. "In other words, it's time for the polluters to pay."

Thomas also emphasized the need for improved air and water monitoring and access to filters in Black communities, as well as investments in green spaces and the creation of community-owned renewable energy infrastructure.

"If we include this type of policy as part of reparations, the reparations policy will be saving lives in Black communities in New Jersey today, as soon as it's rolled out," Sheats insisted.

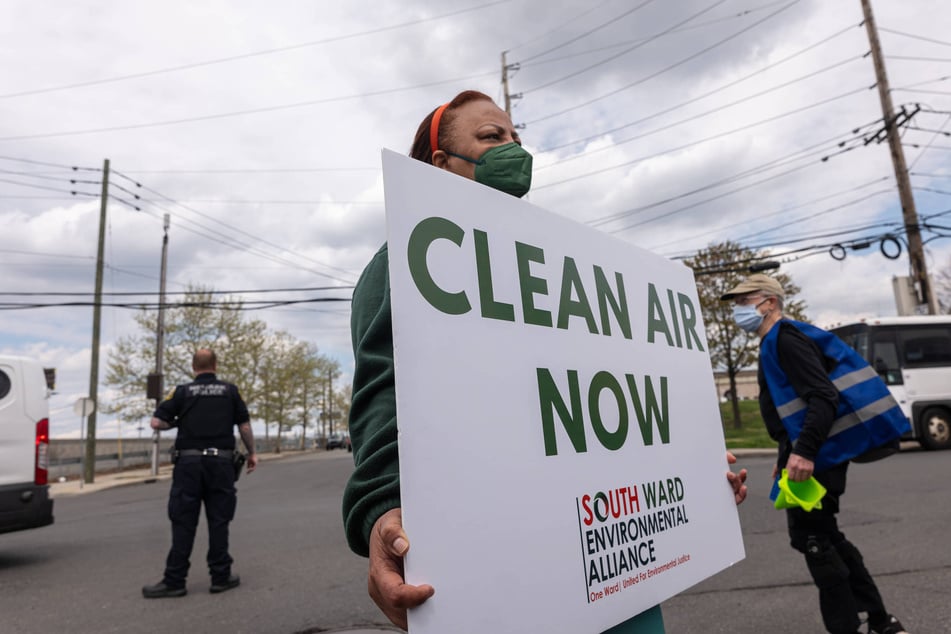

Cover photo: MARK MAKELA / GETTY IMAGES NORTH AMERICA / GETTY IMAGES VIA AFP