Japanese Americans in San Jose share internment testimonies as calls for justice continue

San Jose, California – Japanese Americans in San Jose commemorated their Day of Remembrance for World War II "internment" with testimonies on the historic injustices they and their families experienced – and calls to extend the US redress program to Japanese Latin Americans.

Alice Hikido was nine years old when the attack on Pearl Harbor happened. She was one of 120,000 people of Japanese descent who were subsequently incarcerated in US concentration camps after President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942.

After being forcibly removed from her home in Juneau, Alaska, she and her family were shipped off to an assembly center in Washington and later to a detention center in Minidoka, Idaho. Her father had already been sent to a camp in New Mexico.

One day, Hikido recalled that a young mother in the Minidoka camp disappeared. She and others ran to the river, where the woman had weighted her body down with stones and drowned herself.

"I can remember that and feeling the stress that some people were under and connecting that with my mother, wondering what kind of stress she was under. Would she do something like that at some point?" she recalled thinking.

Other survivors were too young to remember what things were like at the camps, but the experience has impacted their life immeasurably nonetheless.

Tom Oshidari was born in the camp at Rohwer, Arkansas. Though he said he didn't understand the significance growing up, he has gradually come to terms with the fact that he has been a victim of the forced incarceration campaign.

For Oshidari, the losses were more than physical: "It closed the door to our family history because not only did my parents not talk about the incarceration, but they really didn’t talk about the past in general. It was not until it was too late that I really considered my parents to be more than just my parents, but to be people who had stories to their lives."

"Unfortunately, those are stories that I am never going to know."

Remembrance and redress

In 1988, the US government granted $20,000 in reparations to each surviving US citizen of Japanese descent who had been incarcerated during the war and issued an official apology for internment through the Civil Liberties Act.

Activists fought hard to raise awareness of Japanese Americans' experiences during World War II and the lingering trauma caused by the incarceration campaign.

But despite the myriad harms – tangible and intangible – Japanese Americans have faced since internment, they apparently still receive pushback that they are "not deserving" of reparations.

"Those people don’t really understand what we went through," said Eiko Yamaichi, who was incarcerated in Rohwer, Arkansas . "They don’t understand all the hardship that we had to endure."

Yamaichi herself was forced to give up her dreams of a college education outside the camp in order to take care of her mother and brother.

"We managed, but when people say we had it good in camp, they’ve got another thing coming. We tried to make it livable," she insisted.

When asked how he responds to such criticisms of the redress program, Oshidari challenged, "If you ask anybody, would you be willing to uproot your life, leave everything behind for an undetermined amount of time, be shipped off to an undetermined place, and be vilified as undesirable and treacherous people, and for that, 40 years later, you get an apology and $20,000, would you make that trade off?"

"I certainly wouldn't," he said. "It should never happen. It should never have happened. It should never happen again."

"Phase 2" of the redress campaign

But some people didn't get even that compensation.

Among the more than 120,000 people of Japanese descent incarcerated during World War II, over 2,200 were kidnapped from Latin American countries and forcibly taken to camps in the US for the purpose of hostage exchange with Japan. The process was facilitated by the US Justice Department and military.

Many Japanese Latin Americans were deprived of their passports and ID papers, and following the war were denied the right to return to their homes.

When the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 passed, Japanese Latin Americans were not included in the provisions. The US government said that, as they were "illegal aliens," they did not qualify for compensation.

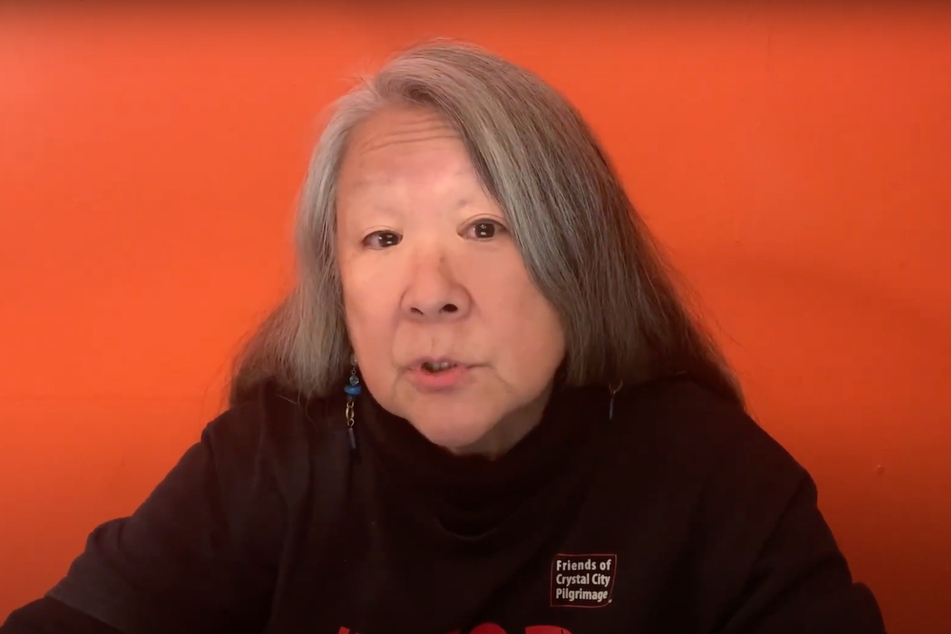

Grace Shimizu, an Oakland resident, testified that her father was a Japanese immigrant in Peru who was forcibly removed from the country and incarcerated in a concentration camp in Texas.

Now she serves as director of Campaign for Justice: Redress NOW for Japanese Latin Americans (CFJ) and of the Japanese Peruvian Oral History Project. There is a very clear objective to her work: "We want justice. We want the US government to be accountable for the civil and human rights violations, the war crimes, the crimes against humanity that it perpetrated against our families in World War II."

Shimizu and others have been fighting for years for US reparations, testifying before Congress, filing lawsuits, and more, but there has yet to be any "proper justice" for people like her and her family.

That's why Japanese Latin Americans brought a case before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which Shimizu described as a "venue of last resort when you cannot get justice in your own country." The commission ultimately ruled that the US owes "moral and material" redress to Japanese Latin Americans.

Nevertheless, the Trump and Biden administrations continued to ignore the body's decision.

"Now is the time to bring pressure on the Biden administration to uphold international law and comply with the commission’s rulings," Shimizu declared. "Phase 2 of the historic Japanese-American campaign for redress is underway."

CFJ and other advocates are calling on people of all backgrounds to join their Day of Action on February 24 by signing their petition, donating, and joining a call storm urging the Biden administration to extend redress to Japanese Latin Americans.

"How long must we wait for justice?" Shimizu asked.

Cover photo: Collage: Screenshot/YouTube/Nihonmachi Outreach Committee