"Dream bigger": Japanese-American activists commemorate internment by pushing for Black reparations

Los Angeles, California – On the 80th anniversary of the executive order that led to the forced incarceration of more than 120,000 people of Japanese descent in US concentration camps, Japanese-American activists stressed the need for solidarity in the fight for Black reparations.

On February 19, 1942, in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066.

As a result, tens of thousands of people of Japanese descent were stripped from their homes, separated from their families, and thrown into concentration camps, often referred to as "internment" camps.

The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians held hearings in multiple cities in 1981. During those meetings, Japanese-American victims and their descendants testified on the impact of the forced incarceration on themselves, their families, and their communities.

The process culminated in the passage of the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, which gave $20,000 to each surviving US citizen of Japanese descent who had been incarcerated during the war. President Ronald Reagan also extended an official apology to the victims.

On the 80th anniversary of Executive Order 9066 on Saturday, Japanese Americans around the country gathered for a Day of Remembrance not only to commemorate their own historic pain and fight for redress – but also to throw their weight behind current struggles for Black reparations.

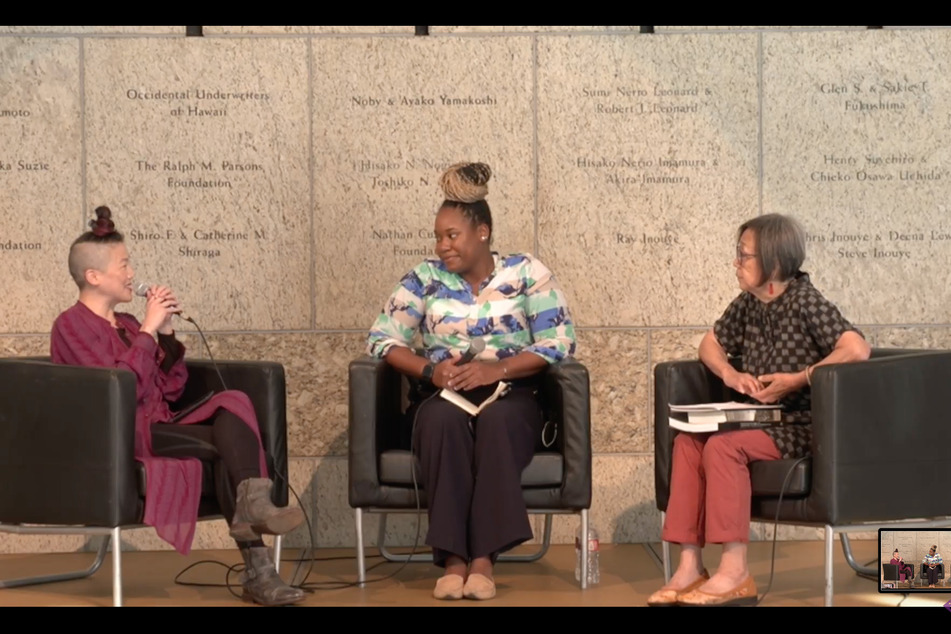

One of those events took place at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, where Japanese-American activists Kathy Masaoka of Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress and traci kato-kiriyama of Nikkei Progressives joined Dreisen Heath, the Human Rights Watch US Program's racial justice researcher.

Masaoka, kato-kiriyama, and Heath have worked closely together throughout the pandemic in their efforts to pass HR 40, the Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act, in the US House, but it was the first time all three met in person.

When asked how it felt to be in the space together, Heath responded, "I’m not sure I have all the words right now. It’s a feeling I’m feeling right now through my body – very visceral – but it reminds me: They come after traci. They come after Kathy. They’re coming after me. Our humanity is connected."

"I cannot see the outcomes of your struggle as different from mine."

History of multiracial solidarity

Throughout the event, speakers stressed the historic cooperation and solidarity among Japanese and Black Americans in the fight for freedom and redress.

Event organizers shared footage of the late Rep. Ron Dellums, a Black-American congressman, giving an emotional speech in support of the Civil Liberties Act at a House hearing on September 17, 1987.

In his defense of the Japanese-American redress movement, Dellums recalled a painful experience in his own childhood when he saw his best friend at the time, a Japanese-American boy only six years of age, taken by force out of their neighborhood.

Masaoka, one of the key leaders of the redress movement at the time, said Japanese Americans learned many lessons from Black leadership as they were fighting for reparations – and always saw their struggles as interrelated. "We knew there was an intrinsic connection among all of us," she remembered.

One year after the Civil Liberties Act passed in 1988, another Black-American congressman, the late Rep. John Conyers, introduced HR 40 for the first time.

Masaoka and other organizers, including people from younger generations like kato-kiriyama, have now turned their energy toward the fight for Black reparations.

That fight, along with related struggles like abolition and ending anti-Asian hate, "are all part of the same spoke of the same wheel of white supremacy," which is why addressing those issues calls for multi-racial collaboration, kato-kiriyama explained.

"Nothing has ever been achieved – in the US specifically – without multicultural, multiethnic, multigenerational work," Heath agreed. "We have to share our struggles. We have to be willing to learn and unlearn."

The ongoing fight for justice

Masaoka, kato-kiriyama, and others have taken that message to heart by "following the lead" of Black reparations advocates and pouring their heart and soul into the ongoing fight for justice.

As a result of their and countless other advocates' hard work, HR 40 now has 217 confirmed votes in the House – the most it has ever garnered.

But despite the huge amount of support it has on paper, the bill has not been brought to a vote on the full House floor. If it is not passed before December 31, it will reset, and advocates will have to begin the process of drumming up support all over again – perhaps in a much different Congress following the 2022 midterms.

"We’re in a generational defining moment at this apex where we can either come back down or go over the hump," Heath said. "Unfortunately, as much power as we build – we feel like we can go over that hump – but the structures of militarism, the structures of imperialism, are pushing us back down."

She added that "symbolic" gestures alone – like making Juneteenth a federal holiday or placing Black heroes like Harriet Tubman and Maya Angelou on US currency – are "the government’s way out of passing HR 40."

"It’s unfortunate that there continues to be compromise on our backs to avoid this reparations process," she lamented.

Heath and other advocates are urging all Americans to contact House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, and Majority Whip Jim Clyburn – three politicians with the power to bring the bill to a vote. All three have said they support HR 40, but they have yet to prove it with action.

"You have people who are selling a reparations study – a reparations process – to get votes, but not to actually follow through," Heath said. "We have to hold them to their public promises."

Opening new perspectives

Since their involvement in the campaign for HR 40, Masaoka said she and other Japanese-American activists have come to see their own reparations program in a new light.

Stressing that every struggle and time period is unique, Masaoka did share several lessons from the Japanese-American redress movement, including the importance of creating a commission that gathers testimonies from impacted communities – as HR 40 seeks to do.

Initially, Masaoka said many Japanese Americans did not want commission hearings because they thought they would hold up the process of receiving monetary compensation – and they did not want to go through the pain of vocalizing traumatic experiences.

But in actuality, the emotional outlet and the education the hearings enabled "galvanized and sustained the movement for reparations," she said. Many Japanese Americans went "from thinking [the commission] wasn’t going to do anything to it being the most powerful thing ever."

Masaoka also said that seeing the discourse around Black reparations has caused her and others to question whether they had demanded enough for themselves, noting that public education, in particular, was an area that was lacking in the Japanese-American program.

"Some of us didn’t know it was possible, but now I have a different mindset – that we have to imagine that anything is possible, that we have to imagine a new way," she reflected, before turning to the fight for HR 40.

"We did it. It’s possible. We can even dream bigger," she insisted.

kato-kiriyama added that not only is a reparations program for Black Americans possible, but it's also necessary. "The future of humanity is at stake," they said.

Cover photo: Screenshot/Youtube/Japanese American National Museum