FBI raid on African People's Socialist Party slammed during St. Louis hearing: "We aren't safe"

St. Louis, Missouri - Black activists and allies spoke before the St. Louis Board of Aldermen's Public Safety Committee on Wednesday, calling on the city government to stop complying with federal raids on community leaders.

The hearing took place amid discussions about the Dred Scott City of Refuge Resolution, which would make the Missouri metropolis a sanctuary city.

It proposes that St. Louis police and local government refuse to cooperate with federal raids that essentially criminalize the work Black leaders and organizers do to uplift their communities.

The first-of-its-kind measure is named after Dred and Harriet Scott. The couple was denied protection from enslavement in St. Louis in 1846 and later denied US citizenship rights in an infamous 1857 Supreme Court decision.

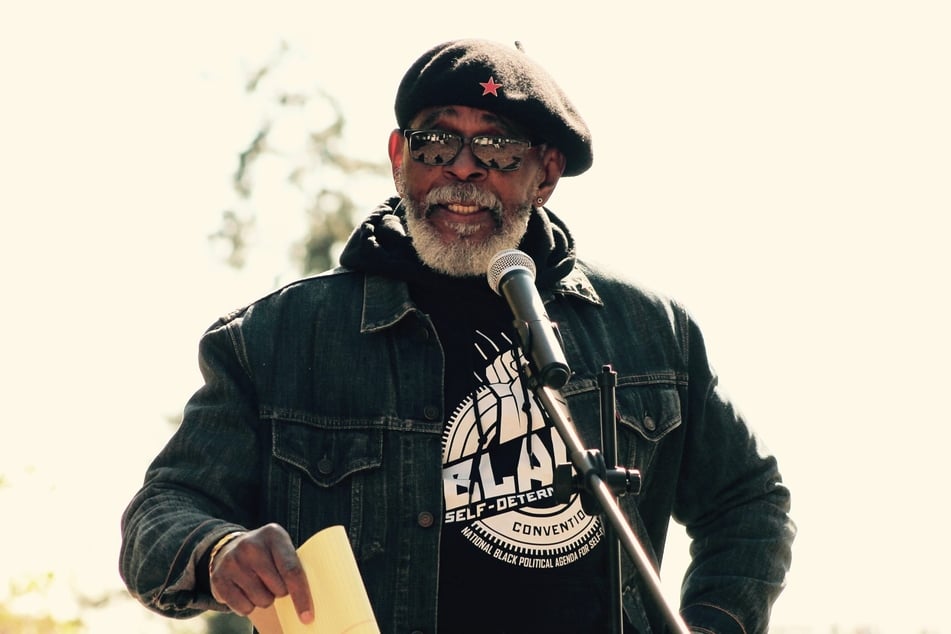

Ward 18 Alderman Jesse Todd introduced the resolution in response to the militarized raid on African People's Socialist Party (APSP) Chairman Omali Yeshitela in North St. Louis on July 29, 2022.

Federal agents, in coordination with local police, stormed Yeshitela's home, deployed drones and flash grenades, destroyed property, and violently handcuffed him and his wife Ona Zené Yeshitela, citing the APSP leader's alleged ties to Russia.

Yeshitela and the party have denied any coordination with pro-Russian actors seeking to influence US elections.

FBI's history of targeting Black leaders under the spotlight

Yeshitela and the APSP advocate for reparations, economic empowerment, and self-determination for people of African descent. They formed the Uhuru Movement in 1972 together with a group of white supporters known as the African People's Solidarity Committee (APSC).

The Yeshitelas and their allies have worked on various community projects through their North City Black Power Blueprint program, including establishing recreational facilities, a garden, and a farmer's market in historically Black neighborhoods.

They see the FBI crackdown on Yeshitela and the Uhuru Movement as part of a long and documented history of colonial suppression of Black freedom struggles.

During the hearing, advocates of the Dred Scott resolution pointed to the FBI's targeting of Black leaders like Marcus Garvey, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture), Freddie Hampton, and others labeled "Black Identity Extremists." They also tied the raid on Yeshitela's home to US intervention in democratic movements across the African continent and the African diaspora.

But ultimately, Yeshitela said the resolution was not about himself or the allegations against him. "It is simply a resolution protecting the presumed citizens of St. Louis by opposing any attacks by the FBI or any federal government [entity] on any individual or organization working for the improvement or upliftment of our community," he said.

"We have been fighting for our birthright in this country for more than 400 years," agreed Alderman Jesse Todd. "All we're asking is that we be able to work in our community, follow the law, and improve our life."

City of St. Louis given an opportunity to send a positive message

Supporters of the APSP see the Dred Scott City of Refuge Resolution as an opportunity to rewrite the narrative in St. Louis.

Coffee Wright, who grew up in Ward 11, said her neighborhood used to be filled with thriving small businesses. Over the years, the city began siphoning resources away from Black communities, leaving her neighborhood a shell of what it once was. Now, things are so bad that her children don't want to raise families in St. Louis.

Thanks to Yeshitela and the APSP, Wright sees opportunities and hope returning to her community, particularly through their youth entrepreneurship and women's health programs. But when the FBI crackdown happened, it sent a different message to Black residents.

Ragina Gray, Midwest regional coordinator of the African National Women's Organization, spoke to the direct impact of the FBI raids: "My kids saw the military vehicle, the armored tank, in the middle of the street. They saw the gun-toting federal agents throughout the neighborhood. This community is already under the surveillance of the police and the state government, with cameras on nearly every block, and now we have a military force in our neighborhood."

"We aren't safe," she continued. "We have no vehicle to pursue our own interests, and this resolution is the beginning steps of correcting that."

Dred Scott resolution supporters face opposition from Public Safety Committee

The debate in St. Louis is part of a national discussion around law enforcement's relationship with Black communities, supporters said.

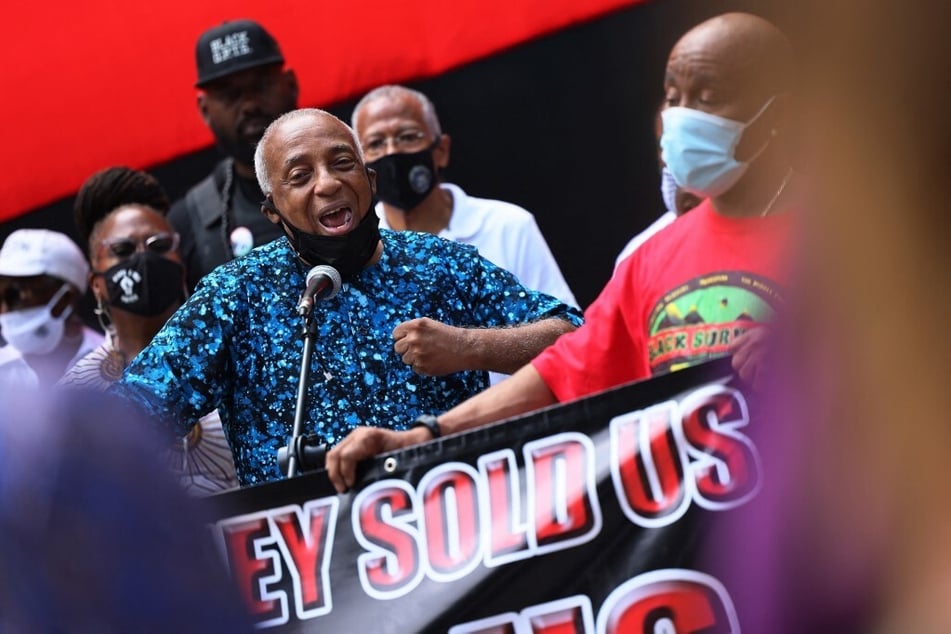

New York City Councilmember Charles Barron, who said he and his colleagues plan to introduce a similar resolution in the Big Apple, urged the committee to pass the resolution: "In the Board of Aldermen, you have an opportunity to say, 'We're going to set a precedent across this nation.' [...] This is going to shoot across the nation and other city councils, and this will be a powerful start."

But when it came time to vote, there were not enough aldermen present in the meeting to reach quorum, and the resolution was unable to move out of committee.

Even though a vote wasn't possible, Ward 23 Alderman Joseph Vaccaro, chair of the Public Safety Committee, voiced doubts over the resolution's feasibility, suggesting that elected officials could lose their positions if they tell local police not to cooperate with the FBI.

NYC Councilmember Barron, however, pointed out that the Dred Scott proposal was modeled on sanctuary city resolutions that his city and other municipalities passed to avoid cooperation with federal deportation raids. Local politicians can express their political will in these matters without violating state law, he explained.

Vaccaro followed up his first objection with the claim that state lawmakers in Jefferson City are "getting ready to take our police away from us" and that the Dred Scott resolution would "absolutely give them more fodder to say it's time to take the police away from the city of St. Louis."

"Mr. Chairman, what we're saying is that the police have already been taken away from you," Yeshitela replied. "That's what the FBI did when they attacked my home on July 29, when they used assault weapons mounted with laser-targeting beams to shoot into my chest to make it clear that they were prepared to kill me."

"You can do the right thing, but you won't. You have to take responsibility for that," he added.

Cover photo: Screenshot/Facebook/Chairman Omali Yeshitela