Could diabetes drug slow progression of Parkinson's disease?

Washington DC - A drug used to treat diabetes slowed the progression of motor issues associated with Parkinson's disease, a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine said Wednesday.

Parkinson's is a devastating nervous system disorder affecting 10 million people worldwide, with no current cure. Symptoms include rhythmic shaking known as tremors, slowed movement, impaired speech, and problems balancing, which get worse over time.

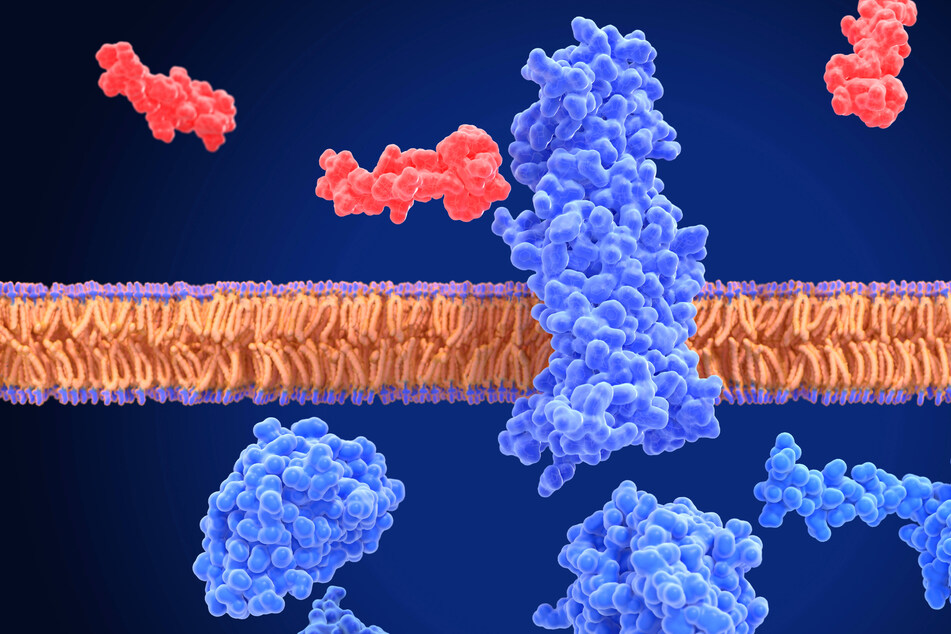

Researchers have been interested in exploring a class of drugs called GLP-1 receptor agonists – which mimic a gut hormone and are commonly used to treat diabetes and obesity – for their potential to protect neurons.

So far, however, evidence of clinical benefits in patients has been limited, and early studies have proved inconclusive.

In the new paper, 156 patients with early-stage Parkinson's were recruited across France and then randomly chosen to receive either lixisenatide, which is sold under the brand names Adlyxin and Lyxumia and made by Sanofi, or a placebo.

After one year of follow up, the group on the treatment, which is given as an injection, saw no worsening of their movement symptoms, while those on the placebo did.

The effect was "modest," according to the paper, and was noticeable only when assessed by professionals "who made them do tasks; walking, standing up, moving their hands, etc." senior author Olivier Rascol, a neurologist at Toulouse University, told AFP.

But, he added, this may just be because Parkinson's disease worsens slowly, and with another year of follow-up, the differences might become much starker.

"This is the first time that we have clear results, which demonstrate that we had an impact on the progression of the symptoms of the disease and that we explain it by a neuroprotective effect," said Rascol.

More research is needed to determine drug effectiveness

Gastrointestinal side effects were common on the drug and included nausea, vomiting, and reflux, while a handful of patients experienced weight loss.

Both Rasol and co-author Wassilios Meissner, a neurologist at Bordeaux University Hospital, stressed more studies would be required to confirm safety and efficacy before the treatment should be given to patients.

Michael Okun, medical director of the Parkinson's Foundation, told AFP that from a practical standpoint, the differences in patient outcomes were not clinically significant, but "statistically and compared to other studies, this type of difference should draw our interest and attention."

"Experts will likely argue whether this study meets a minimum threshold for neuroprotection, and it likely does not," continued Okun, adding the weight loss side effect was concerning for Parkinson's patients.

Rodolfo Savica, a professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, added: "The data so far are suggestive of a possible effect – but we need to replicate the study for sure."

He added that while this study lumped together patients aged 40-75, separating them by age group might have revealed ages at which the treatment is more effective.

The authors of the new study said they were looking forward to the results from other forthcoming trials that may help confirm their findings.

Cover photo: IMAGO / Science Photo Library