Death by incarceration: Abolitionists at UN call for end to "the other death penalty"

Geneva, Switzerland - The United Nations often focuses on capital punishment when assessing countries' human rights records, but this year's Human Rights Committee review of the US shone a light on "the other death penalty" – death by incarceration.

Death by incarceration (DBI) refers to extreme sentencing practices, including life without parole, life with parole, "virtual life" sentences that exceed life expectancy, and other lengthy and indeterminate sentences.

Typically viewed as an alternative to executions, these punitive measures are just another form of death sentence, advocates argued during the recently concluded United Nations Human Rights Committee review of the US.

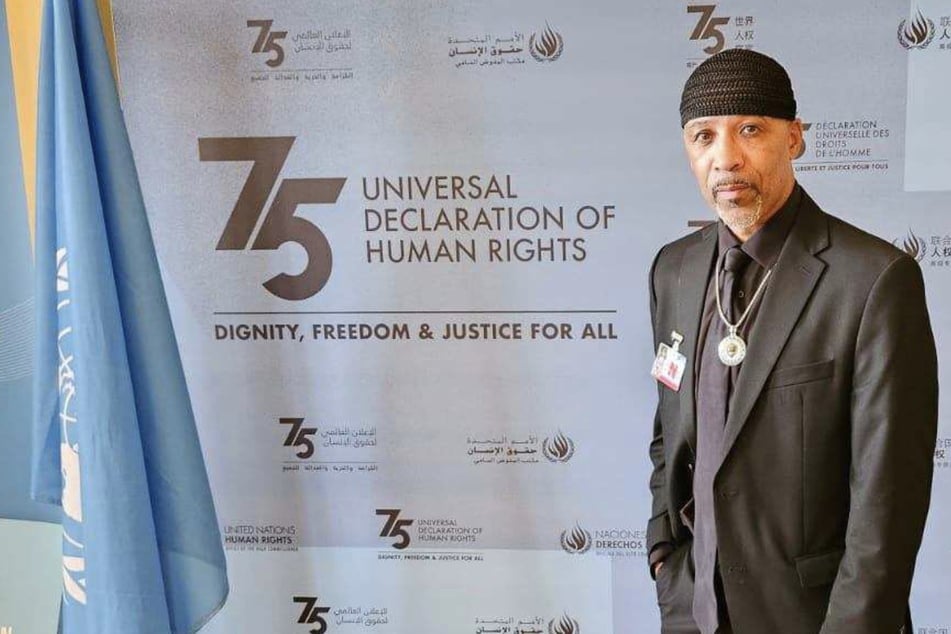

One of the organizers on the ground in Switzerland was Stanley Jamel Bellamy of the Releasing Aging People in Prison (RAPP) Campaign in New York. He was just 23 years old when he was given a 62.5-year minimum sentence in 1987 and didn't expect to go before the parole board until he was 85 – that is, if he managed to live that long.

"Because of my lifestyle, the health conditions, there was no way I was going to get to 85, so it was important for me to recognize I was serving a death sentence," Bellamy said during a panel event in Geneva last week.

What is unique about Bellamy's experience is not the excessive prison time he received as a young man, but rather that he got out. After more than 37 years behind bars, New York Governor Kathy Hochul commuted his sentence in December 2022.

"The United States should be ashamed of themselves because we are the only country that talks about disposable people," Bellamy said. "On an international level, we must pressure the United States and get the United States to understand that people change."

"We are human beings, and we need to be recognized as human beings," he continued. "We have rights, and one of them is not to be tortured because that is a torture sentence."

The racist legacy of death by incarceration

DBI is a pervasive problem that advocates say violates the right to life and right to be free from torture guarantees in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, ratified by the US in 1992.

These extreme sentences are not doled out equally across the board.

Over 200,000 people around the country – nearly one of out of every seven people behind bars – are serving some form of life sentence. Of those, around 46% are Black, although Black people make up only 13.6% of the total US population.

Once inside, incarcerated people are often required to perform back-breaking labor for little or no compensation and subjected to torturous punishments if they resist – practices many view as a direct continuation of the US' legacy of settler colonialism and enslavement.

For Anthony Hingle of the Visiting Room Project, those locked up on life sentences are the "walking dead." He knows firsthand what that feels like, having spent 32 years behind bars in the Louisiana State Penitentiary (aka Angola) – the site of a former slave plantation.

"You actually have a death sentence, it's just a slow death. While you're serving it, they're going to benefit from it because they are going to slave you for decades," Hingle said.

"We're doing same work our ancestors were doing decades ago," he added. "These DBI sentences, they were created from tough-on-crime platforms and also to keep the slave trade going."

Organizing for freedom from the inside out

Surviving the injustice of DBI is what motivated several of the advocates at the UN to push for change.

"We're never getting out unless we are all fighting together. We're all doing a death sentence if we don't change it with each other," explained Kelly Savage-Rodriguez, who did 23 years on a life without parole sentence before getting released in 2018.

While Savage-Rodriguez and the California Coalition for Women Prisoners were taking on institutional violence in the Golden State, similar efforts were underway in other prisons all around the country.

Robert Saleem Holbrook, executive director of the Pennsylvania-based Abolitionist Law Center, was a teenager when he was given a life sentence for involvement in a 1990 drug-related murder, even though he didn't pull the trigger. When he got to prison and saw hundreds of people who looked like him, he came to believe the problem was by design. Meeting Black political prisoners who had been organizing to better their communities when they were incarcerated only cemented his resolve to fight back.

"We realized we needed someone to speak for us, but the prison and non-profit industry weren't going to do it," Holbrook determined. That understanding kick-started his journey to study law as a tool to advocate for himself and others locked up on unjust sentences.

"When you go to prison at 16 years and 124 pounds, you have to learn to punch above your weight," he said.

Demanding an end to death by incarceration on the world stage

Though once unimaginable, release from prison was not the end of the journey for Bellamy, Hingle, Savage-Rodriguez, or Holbrook.

All four former lifers shared their personal stories in Geneva to elevate the dire conditions facing tens of thousands of currently incarcerated people in the US today.

UN Human Rights Committee members were clearly moved by the testimonies, directly referencing death by incarceration in their remarks and requesting the US government delegation explain the overrepresentation of Black and Indigenous people in imprisoned populations.

On top of that, Biden administration officials were asked to share what steps they are taking to reduce the use of solitary confinement in prisons, including for juveniles, and to ensure such punishments are limited to a maximum of 15 days.

Civil society representatives from NGOs around the country expressed frustration with the US responses to crises facing their communities, which came across to many as overly general and scripted. Nevertheless, they were pleased that UN committee members heard their demands for a comprehensive transformation of the US carceral system and pressed the issue during questioning.

The Human Rights Committee could provide further momentum to the abolitionist cause by calling for an end to death by incarceration in their concluding observations and recommendations, scheduled for release on November 3.

Cover photo: Screenshot/Twitter/AbolitionistLC