Alabama father and son duo take on the school-to-prison pipeline at the United Nations

Geneva, Switzerland - CJ was just 17 years old when he was forced out of Paul Bryant High School in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, without proof of any infraction. That incident marked his life and started a fight for justice that led him all the way to the United Nations.

In November 2022, school officials found marijuana in a car CJ was riding in with several other students after missing the bus.

He maintained the weed was not his, and a police investigation led to charges against another student, not CJ. Nevertheless, he was placed on a two-month in-school suspension and banned from playing baseball.

The teen never had an opportunity to plead his case, nor were his parents permitted to sit down with administrators to discuss what was happening to their son.

The administration ultimately recommended CJ be sent to an "alternative" school – institutions that are often understaffed and under-resourced.

"It’s pure hell witnessing your child going through something and not deserve it," CJ’s father, Cory Jones, told TAG24 NEWS.

As the suspension dragged on, CJ struggled with anxiety and depression, questioning whether he deserved to live.

"Before the situation happened, I had high hopes of going to college, baseball, just ready for the next step to make myself proud, make my family proud," he recalled.

Many of those dreams were shattered by his Alabama high school's extreme disciplinary measures and denial of due process.

"I trusted the school system, so when that happened, all my trust in everything went away," CJ said.

Fighting for justice on the world stage

CJ completed his high school degree requirements in homeschooling, missing his opportunity to walk the stage with his peers on graduation day.

Though those lost memories could not be regained, Jones had aspirations of clearing his son's record and at least securing an apology from the administration.

That didn't happen.

With his father’s support, CJ brought a lawsuit in February accusing Tuscaloosa City Schools of unlawfully depriving him of his right to education. The filing came just days before his 19th birthday.

"Now that I look back at it now, I'm glad that I went through that," CJ reflected. "Otherwise, me and my dad wouldn't be sitting here right now."

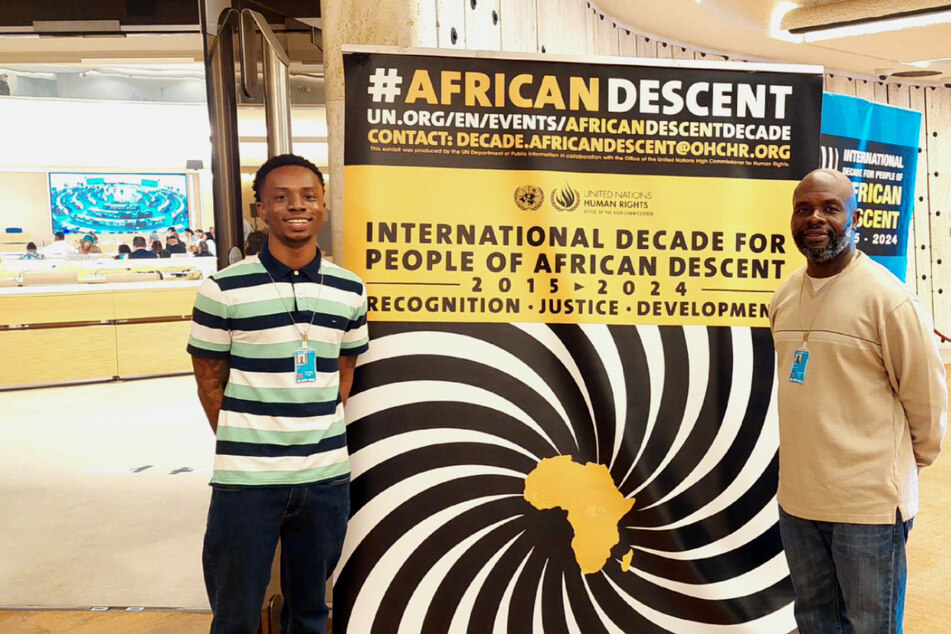

Both father and son are currently with the Southern Poverty Law Center at the United Nations in Geneva to testify before the Permanent Forum on People of African Descent (PFPAD) on anti-Black discrimination in the US education system. The experience has been unforgettable, allowing CJ and his family to share their story on the world stage.

"Freedom is not just you helping yourself," CJ said, in the spirit of the late Toni Morrison. "Freedom is when you're helping somebody else to be free, so I'm also talking for kids who can't speak or don't have the support or the funds or the daddy or the mama or the cousin or anybody."

Uncovering Alabama's legacy of racial discrimination

The PFPAD is tasked with developing an international racial and reparatory justice framework to address the ongoing legacies of enslavement and colonialism for people of African descent.

CJ and his father see their experience in Alabama's education system as directly tied with the US' history of anti-Black racism.

Jones said the highest-level administrators at CJ's school were white, as were the people represented in pictures and statues at the Alabama Capitol, where he went to advocate for his son. At the same time, many of the service and secretarial workers at the state legislature were Black.

This dynamic has stark effects. An Al.com analysis found that Black students in Alabama were two times more likely to experience classroom removal in 2018-2019, which translates to higher dropout rates and greater likelihood of entering the criminal-legal system – a phenomenon known as the school-to-prison pipeline.

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, Black Americans account for over 37% of the US prison population, despite making up just 13% of the country's overall population.

"The Bull Connor days are still here – without the dogs. They're whooping us with the pen and pencil and sending young Black men into the penal system," Jones said.

Lighting the spark for global change

The UN's PFPAD has provided an opportunity for people across the African continent and diaspora to come together to pursue transformative solutions to persistent inequities.

Jones hopes his and his son's testimonies will send a message to the PFPAD to keep its eyes on Alabama as it examines threats to education impacting people of African descent worldwide. He also wants to animate others in similar circumstances to speak out in their quest for justice.

"I hope people have an idea of what it’s like if men stand up, if true men stand up for their kids, their families, their jobs, or whatever it may be," Jones urged.

CJ also wants to light a spark for change.

"I hope that my story can touch lives, and I hope that when I walk out today, whether it's the people on the podium or in the audience, I hope that somebody in this room can make a change, not only for their country but worldwide," he said.

"If all of us come together worldwide – no matter if you're pink, red, purple, brown, whatever color – if we all come together and start cooperating with each other, everybody will be at the top."

Cover photo: TAG24/Kaitlyn Kennedy