US revokes authorization for Covid drug in blow for vulnerable people

Silver Spring, Maryland - The US Food and Drug Administration has withdrawn its provisional support for the use of Evusheld, a medication that was once a valuable tool for preventing patients with weakened immune systems from becoming severely ill with Covid-19.

With new viral variants increasingly adept at defeating Evusheld, the FDA said the biological drug should no longer be used.

The FDA decision marks the end – at least for now – of a medication that had helped restore some normalcy to the lives of cancer patients, transplant recipients, and others who either could not be vaccinated against Covid-19 or whose immune systems failed to make a good response to vaccine. As many as 3% of the US population – 7.2 million adults – is thought to have immune deficiencies that put them at risk of becoming severely ill or dying if they are infected with the pandemic virus.

"It's a really sad time," said Dr. Camille Kotton, an infectious disease doctor at Massachusetts General Hospital who cares for people with impaired immunity.

For her patients, she said, "it was kind of like being told the seat belts in your car won't work anymore, and we're not going to be able to replace them with anything."

Evusheld has become increasingly less effective against the coronavirus

In recent months, nine new subvariants of the dominant omicron strain have proven capable of sneaking around Evusheld's defenses. Collectively, those subvariants now constitute more than 90% of SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus specimens circulating in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The result: after 15 months in the nation's armamentarium against Covid-19, a medication that US taxpayers spent at least $1.58 billion to develop and produce has become largely ineffective. However, the FDA said its authorization for the drug would resume if at least 10% of coronavirus specimens in circulation are susceptible to it in the future.

Evusheld is the commercial name of an AstraZeneca drug that combines two monoclonal antibodies, tixagevimab and cilgavimab. In a statement Friday, the British-Swedish pharmaceutical giant said it is testing the safety and effectiveness of a new antibody medication to protect people with weakened immune systems, which it hopes to field in the latter half of 2023.

When Evusheld became available to patients just more than a year ago, its protection allowed many immunocompromised patients to emerge from isolation for the first time since the pandemic began.

It was expected to be administered to patients who needed it every six months. But some never got their first jab, and many did not get their second, before changes in the coronavirus rendered it ineffective.

"We're mourning the official death of what had been a really good tool," Kotton said.

Many doctors had already stopped giving patients Evusheld

Many doctors had already accepted that Evusheld's time had passed.

Physicians at UCLA Medical Center and its satellites stopped giving it to their transplant and chemotherapy patients in December. That is when the omicron subvariant known as BQ.1.1., which had found a way to circumvent Evusheld's protection, became dominant across Southern California.

"It is unfortunate," said University of California, Los Angeles infectious disease physician Dr. Tara Vijayan. But, she added, "we were surprised the FDA waited so long to pull it."

Thanks to the relentless rate at which new coronavirus variants have emerged, a passel of Covid-19 drugs based on bioengineered monoclonal antibodies have become obsolete.

Since November 2020, when the first such treatments for Covid-19 won the FDA's provisional support, six have been rendered useless by genetic changes in the coronavirus.

It began with the emergence of the Delta variant in March 2021, and the arrival nine months later of the omicron variant – which itself has splintered into 18 subvariants – has wiped out the rest.

FDA has withdrawn most monoclonal antibody treatments

Since April 2021, the FDA has withdrawn its emergency use authorization for all monoclonal antibody treatments used as therapies for Covid-19 except for tocilizumab, which continues to be used in some hospitalized patients.

As UCLA doctors watched one after another of their monoclonal antibody therapies fail, "we always advised a measure of caution," said Vijayan, the health system's medical director of adult antimicrobial stewardship. "We were always waiting for the variants and the resistance that would come with them."

The virus's triumphs over these sophisticated therapies has left all Covid-19 patients with a dwindling store of rescue drugs. But for patients with compromised immunity, the situation is even worse.

The virus' incessant shape-shifting has more completely demolished the store of effective drugs that can save them from severe illness or death with Covid-19. Many cannot take the antiviral Paxlovid because it interacts with their other medications. That leaves them with the less effective antiviral molnupiravir and the drug remdesivir, which must be infused daily – usually in a hospital – over three days.

The dearth of drugs available for patients with compromised immune systems has renewed interest in convalescent plasma, an old-school version of antibody therapy first explored in the opening days of the pandemic. As COVID-19 therapies for these fragile patients have dwindled, several medical societies have recommended a return to the use of blood products drawn from previously infected patients who have recovered.

A recently published systematic review of clinical trials suggested that convalescent plasma could help prevent death in hospitalized Covid-19 patients with impaired immunity. A British clinical trial is currently testing the use of "Vax-Plasma" – plasma from vaccinated people who had breakthrough infections and then recovered.

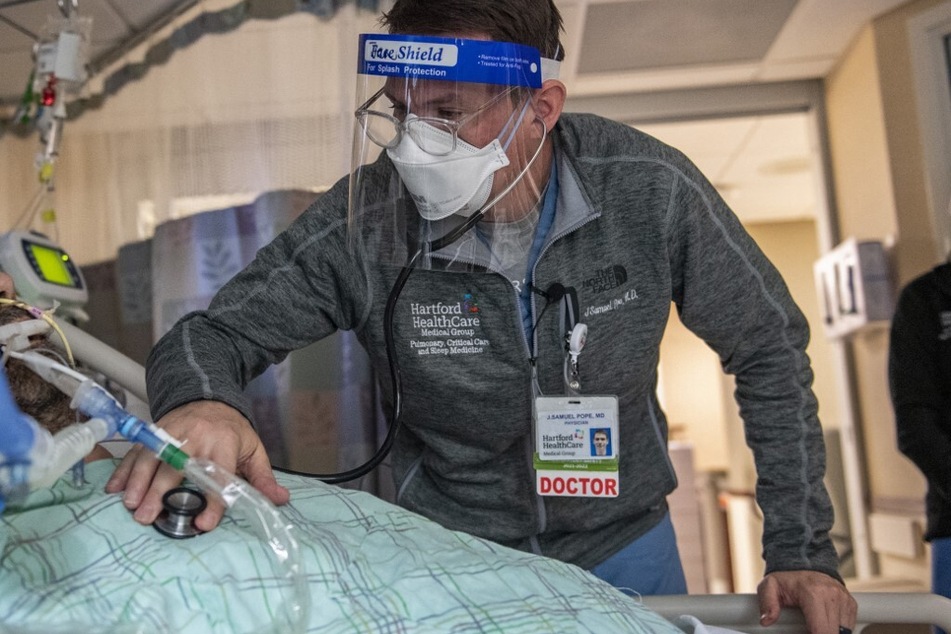

Cover photo: JONATHAN NACKSTRAND / AFP